The Shell Game:

Unraveling Molluscan Mysteries

Cataloging and digitizing McKissick’s historic shell collection is part of the larger Historic Southern Naturalists project. The collection of mostly snail and clam shells was believed for decades to have been donated by noted amateur Charleston conchologist, William G. Mazyck. Recent research suggested, and was later confirmed, that the collection was amassed by 19th century naturalist Lewis Reeves Gibbes, Mazyck’s cousin and mentor. After his death in 1894, Gibbes’ daughters sold the collection of more than 4300 shells to the university and Mazyck organized and identified the specimens. The collection of snails, clams, oysters, and other molluscs are presented here along with their documentary labels.

Mollusca

The biological group Mollusca is made up of invertebrates, or organisms with no internal skeleton, that are found in marine, freshwater, or terrestrial ecosystems. Molluscs usually secrete a shell made of calcium carbonate; these shells are often used to differentiate species and are highly collectible. The group includes snails and slugs, clams and oysters, squid and octopi and many more diverse creatures.

Click on the six classes of Mollusca below to see examples and learn more.

This diverse group of invertebrates, commonly known as snails or slugs can be found in marine, freshwater, and terrestrial environments. The name “gastropod” comes from the Greek roots for stomach and foot, referencing the location of the organism’s gut below the foot. Snails typically have a shell that is designed with an apex at the top that coils around an axis toward a large aperture. The swirls along the shell are referred to as “whorls” which can be ornamented with nodules, color bands or spines. Slugs have no shell, so are not included in this exhibit.

Marine

Freshwater

Terrestial

This class of marine and freshwater molluscs includes clams, oysters, mussels, and scallops. The group is characterized as having two shells, or valves that are connected by a hinge, thus the name “bi-valve”. The interior of each valve contains muscle scars and hinge teeth that are easily seen once the soft tissue is removed. The exterior can be smooth with simple growth lines or highly ornamented with heavy ridges, spines, and even color stripes.

Clams

Mussels

Oysters

Scallops

This class of molluscs includes squid, octopus, cuttlefish and nautilus. These soft bodied animals are exclusively marine and are composed of at least 8 arms connected directly to the head. Cephalopods are bilaterally symmetrical with an elongate form, beginning with tentacles or small arms. A beak leads into the mantle (head) and the top of the mantle can have stabilizing fins shaped like a teardrop. Cephalopods are notable for squirting ink when threatened, changing skin color and having complex eye structures. These creatures are considered the most intelligent of all invertebrates.

The “tusk shells” or scaphopods are a group of infaunal molluscs, meaning they burrow into the marine substrate and live buried in soft mud or sand. The shell is slender and slightly curved with openings at both ends. While the group is somewhat enigmatic, fossil examples have been found in rocks more than 350 million years old.

The chitons, or polyplacophora, are exclusively marine and possess eight overlapping shell plates or valves. Overall, the oval-shaped body is flattened and elongated, with shell plates only present on the dorsal (or back) surface. The valves may have spines, scales or hairs around the margin.

As the class name suggests, this group of molluscs has no shell, but instead secrete spicules that give the animal a shiny appearance. Because these worm-like animals have no hard parts, they are not represented in this collection.

Importance of shell collections and collectors

The Lewis Reeves Gibbes shell collection contains just over 4300 shells. Shells are interesting to look at and most everyone has picked up one or two on a beach or a hike; but what makes a shell collection/collector from the 1800s important historically and scientifically?

The biological field has many uses for a shell collection. Think of a tree, once cut, the rings reveal many details about the tree, including climate, water availability, and the soil content during the tree’s life span. Scientists can utilize the shells of molluscs in the much the same way. Marine and terrestrial snail shells are composed of elements the animal draws from its environment. These chemicals tell the history of each organism’s environment during its lifespan, and thus can inform scientists about past environments and provide important baselines for climate change research.

Want to know more? The ornamentation of a shell provides information on the climate in which then animal lived. Warm shallow ocean environments have lots of calcium carbonate available, and organisms tend to be highly ornamented. Molluscs from colder or deeper ocean environments tend to be less ornamented.

Additionally, a shell can hold isotopes of elements such as oxygen that inform about glaciation history. When a shell is crushed and analyzed for oxygen isotopes, scientists get a sense of past ocean temperatures. When compiled with information from other climate proxies, we get a more accurate history of global temperature. Historic environments can be reconstructed using data from shells, and in certain cases, when species have become extinct, scientists can examine any shifts in climate and environment that may have contributed to the extinction.

Shell collections can be as important as the individual shells if proper attention is paid to associated data related to collection localities and the historic context of the collector. During the 19th century many amateur collectors expanded their collections by exchanging specimens. Therefore, original labels including the location of collection and collector’s name can provide current researchers excellent information on how samples have traveled around the world.

Lewis Reeves Gibbes

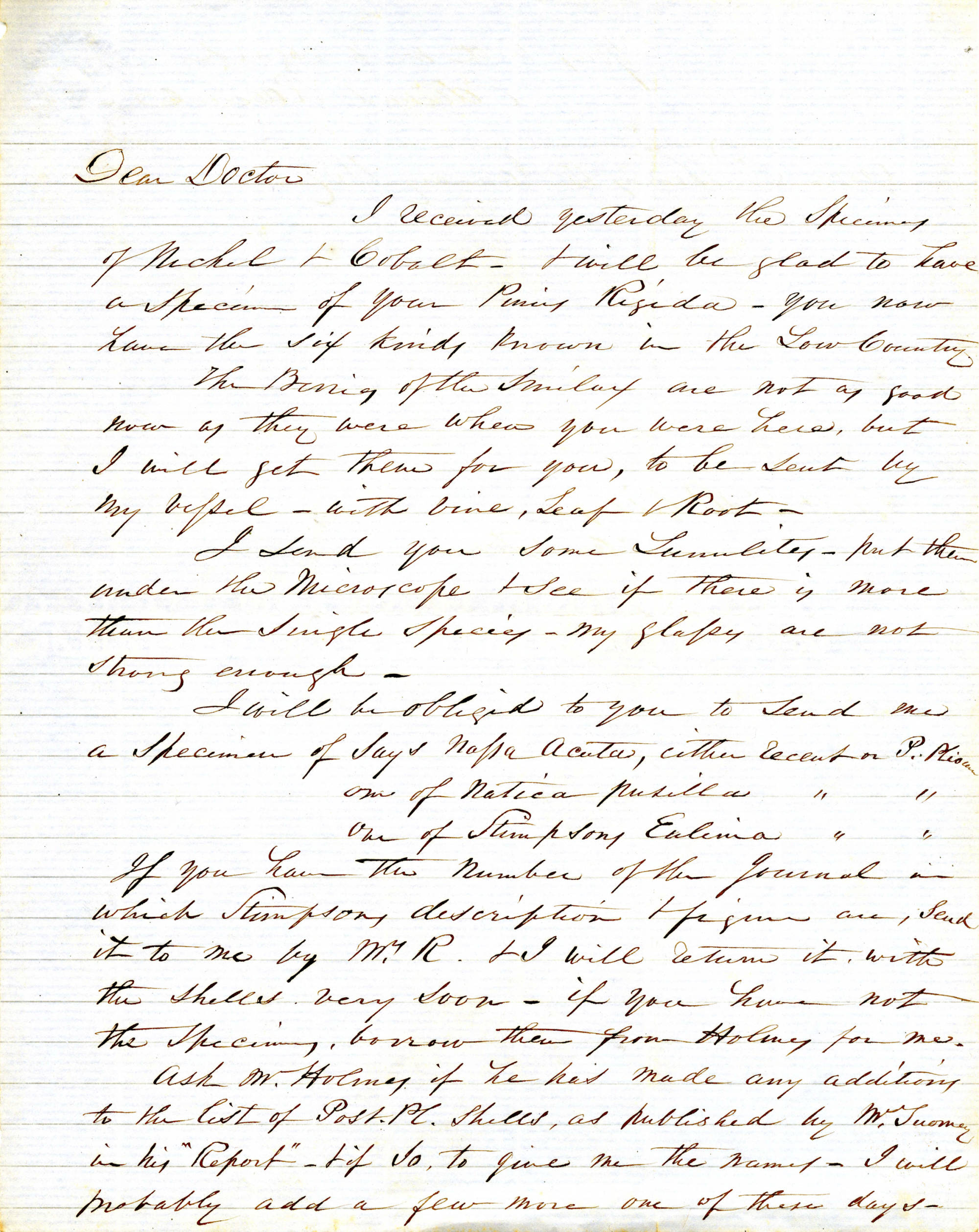

Letter to Lewis Reeves Gibbes from Edmund Ravenel

January 15, 1857

Courtesy of South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia, S.C.

Early naturalists grew their collections by trading with other naturalists, often in the form of parcels sent through the mail. In these letters, Edmund Ravenel writes to Lewis Gibbes about plant and shell collections they were studying.

Click on the letter to see the both letters and the full text transcriptions.

Photograph of Lewis Reeves Gibbes, by J. A. Nowell, 1886.

Lewis Reeves Gibbes, the eldest of eight children, was born August 14, 1810 in Charleston, South Carolina. Lewis excelled in his studies early in life and was a student of Dr. Thomas Cooper’s at South Carolina College, graduating with honors in 1829. Two years later, he returned to SCC as a mathematics tutor (1831-1834) and instructor (1834-1835). While in Columbia, he began a study that resulted in the publication of the Catalogue of the Phoenogamous Plants of Columbia, S.C., and Its Vicinity. In 1836, Gibbes completed the medical program at the Medical College of South Carolina in Charleston. He studied abroad in Paris after medical school, and upon his return to Charleston began what would be a fifty-four-year career with the College of Charleston. Exacting but endearing, Gibbes was a professor of mathematics, chemistry, physics, and astronomy. Lewis Reeves Gibbes was a well-connected and prominent scientist who enjoyed many opportunities through the American Association for the Advancement of Science. During the mid-nineteenth century, Gibbes was a leading expert on American crabs and authored the first publications on South Carolina’s marine algae. An avid collector of the natural world, he described his own cabinet of crustaceans in 1850 as “the largest I believe at the South.” Many consider Lewis R. Gibbes to be one of South Carolina’s most versatile scientists. After his death, Gibbes’ shell and mineral collections were purchased by the University of South Carolina from his daughters.

Shell Collecting

Conchology is the study and collecting of marine, freshwater and terrestrial shells. Preserving shells entails cleaning, labeling and safely storing them in cabinets or drawers. Conchology is important because it can give details into the taxonomy and evolution of particular species. Without conchology and shell collecting, there would hardly be any research into the various species of molluscs. Today shell collections are built similar to how they were formed in the past. Specimens are collected, cleaned, cataloged and analyzed for their speciation and any other important details a researcher needs to look for. Shell collections are often kept behind the scenes inside of museums for research purposes.

Shell collecting in the past

Today’s hobby was once a burgeoning scientific endeavor brought on by the age of exploration.

Naturalists, like Lewis Reeves Gibbes, documented new species in new locales and traded specimens with other scientists around the world. Most naturalists maintained personal cabinets of specimens and often published their discoveries in catalogs or presented their findings at annual meetings of various scientific societies. Edmund Ravenel speaks of publishing his catalog in many letters written to Gibbes.

Current practice

Today shell collecting is typically a hobby, akin to coin or stamp collecting. The beauty and variety of seashells draw many enthusiasts. It is important to collect ethically and Hal Brindley along with Travel For Wildlife has put together a guide to ethical shell collecting.

Here are a few of the most important points:

- Do not take anything alive.

- Leave spiral shells for new inhabitants, the hermit crabs.

- Take less or take photos! Shells (even broken or uninhabited) are important to the ecosystem.

About HSN

In 2016 McKissick Museum applied for and was awarded an Advanced Support for Innovative Research Excellence (ASPIRE) award from the University of South Carolina. The project objectives were threefold:

- Digitize objects and associated archives of significant historic collections from the University of South Carolina’s collecting institutions A.C. Moore Herbarium, McKissick Museum, and South Caroliniana Library;

- Merge those digital records of natural history collections into a comprehensive, cross-referenced database accessible to the public online;

- Utilize newly created digital images to enhance exhibits through interactive touchscreens;

In 2018 the project was expanded through funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS). This new phase of the project added the archives, specimens, and objects related to Thomas Cooper, Lewis Reeves Gibbes, AC Moore, as well as materials held at The Charleston Museum. Additionally, 3 digital exhibitions featuring McKissick’s collections were developed.

These archival collections not only document the 19th-century investigations of the natural environment in South Carolina, but they also illustrate the establishment and advancement of the field of natural history. The material collections, including botanical, fossil, and mineral specimens, exemplify the natural world that existed two hundred years ago, and are sometimes the only representatives of these taxa in existence due to extinction and loss of geologic localities. Additionally, these objects are not always appropriate for exhibition due to their sensitive or fragile nature; digitizing them will allow for use in on-site exhibitions as well as an online resource.

Other features of this website include video vignettes and a timeline of these naturalists’ investigations. This resource is in no way complete; however, it focuses on the naturalists associated with the University and includes significant events in US and global history. Rather than highlighting historic naturalists, the video vignettes feature modern researchers from the University as they demonstrate the collection, documentation, and preservation of objects for future generations.

Explore the HSN site here.

Acknowledgements

This project is a collaboration of the following UofSC organizations and the Charleston Museum and was made possible in part by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (Project # MA-30-18-0048-18).

McKissick Museum

Christian Cicimurri

Linda Smith

Giordano Angeletti

Heather Cain

Eric Friendly

Savannah Keating

Jay Loy

Nate Price

Katy Self

Elliott Sloan

Meghan Teumer

Taylor Turbyfill

Digital Collections

Megan Oliver

Alex Trim

Matthew Simmons

The Charleston Museum

Matt Gibson

Jennifer McCormick

Jessica Peragine